Some parents are super-heroes.

That statement is, by now, an axiom.

But there's a critical element that's often overlooked when the axiom is expressed. And that's the "some." But, with even a slightly-deeper analysis, it becomes easy to see why so many people miss that part.

So many people want desperately to believe that their own parent is uniquely special. It' can often be difficult to look back on the people who, in one or another - whether in a few ways or many - helped make you into the person you are today ... and find them wanting in your eyes.

And, even when it's not difficult to do so ... it's usually painful. And gender-nonconformers, most especially, know this all-too-well. And it's hard for us not to think of this as our fault. And it creates a lot of guilt - because we feel like we've failed our parents ... and, too, our fathers. We feel like we didn't turn out quite how they wanted us to be - and we're often right.

We who were transgirls weren't the happy, carefree, "normal" boys our parents foresaw - we aren't kids who will be afforded the kind of childhood our parents envision for us.

And that concept extends toward any kind of childhood where A doesn't exactly equal A. Kids like that - we're different. We're bizarre. We're inexplicable. We're difficult. We're challenging. We're blasphemous. We're weak. We're puzzling. We're complicated. We're wrong. We're dangerous. We're weird.

In other words ...

... we're mutants.

And a mutation, by virtue of their unfamiliarity to a parent, is often scary. And it's that fear that leads to everything else, to all the problems a parent faces. Look at every one of the descriptors in the paragraph above and consider them. Add " ... because we're scary" to each one, and realize that those are the feelings that run through many parents' minds when a transgirl reveals who she really is to the people who are raising her.

Because, suddenly, all bets are seemingly off for the parents of a transgirl. Depending on the environment in which the parents, themselves, were raised, the whole set of preconceived ideas about what it means to be a parent might go out the window. It's uncharted territory for many parents, dealing with their peculiar and particular little mutants. This, too, is scary - because, often rather suddenly, the trail has no signposts.

And it's especially difficult, too, because transgender children are often trying to figure out who they are in life even as their parents are dealing with all these issues of unfamiliarity and fear. And, when we figure it out, that often becomes even more frightening for our parents - because they start thinking about the foundations upon which our future will be built - regardless of the legacy our parents want to leave behind in the world.

And so come the question every parent asks when they find out their child is gender-nonconforming. And these two questions can get the average parent completely stuck. They're like gateways that not everyone can pass through. They define the differences - when it comes to kids who are gender-nonconforming ... between average parents, good parents, great parents ... and parents who are super-heroes.

And the first question is often the most painful for the parent:

Am I the villain in all of this?

This process of thought is, of course, predicated on the idea that there has to be a villain in a situation where a parent has a gender-nonconforming child.

And bad parents don't often get beyond this point. Bad parents don't even get to the second question. They get lost in the first one. They end up spending a lifetime of regret looking for a villain to blame for their gender-conconforming child.

And that's tragic - because there there isn't a villain. There's absolutely no villain - not even an X chromosome that ends up turning into a Y when it shouldn't. There's no villain, even when a brain's function and structure and behavior matches one gender's but other parts of the body match another's. There's no malice in the factors that lead to a kid who doesn't conform to his gender. And there's no villain, even when a child is facing challenges in the world that the parent never expected they would have to face.

But good parents emerge out of the miasma of that question in recognizing that it's nobody's fault - but also recognizing that a gender-nonconforming child surely will face challenges in a world that isn't built expressly for gender-nonconforming kids.

Which leads these parents to the second question.

What do I do now?

And it's true that, even after reaching this second gateway into understanding, many parents continue to blame themselves - only, for those who make it this far, it's often more about not having all the answers than guilt for what has actually happened. These are parents who want to know, in advance, what all the right answers are in raising their child ... and who feel the extra pressure of the fact that their child is gender-nonconforming.

And parents who are more than good - who are truly great parents - realize that there aren't any easy answers to that second question. And great parents accept this even as they suffer through those difficult times with their kids.

And all kids - whether or not they conform to their gender - are going to be disappointed in their parents from time to time - even if their parents are great parents.

But kids are smart.

Kids know when parents give up ... and when parents fight on, to get it right.

And kids know what real apologies - and real commitments - from parents really sound like.

But even the best-made plans don't make for super-hero parents.

Because being a super-hero parent isn't about getting this step right. That makes for great parents, yes.

But superhero parents? The gateway into becoming a super-hero parent is tougher than that. It's a bigger responsibility. It requires more energy and more work and more commitment and more dedication even with the recognition of the risks involved - even at great personal cost.

So - what's the critical difference between these gateways?

Average parents have a kid. Good parents make the most of the life they and their kids are given in this world. Great parents fight for their kids. But real, honest-to-goodness super-hero parents? They're the ones who take the experiences of their own parenting lives - all their joy, pain, tragedy, triumph, hope, fear, anxiety and strength ... and use all that energy to try to make the rest of the world outside their homes a better place for not just their kid, but all kids.

But that leads to a question of my own: what is it that makes these super-hero parents capable of being super-heroes in the first place?

It's certainly not so simple an explanation as an easy, one-word explanation like "kindness," "generosity," or "fairness."

Super-hero parents can say things kids don't always want to hear. They can - and do - force difficult truths out into the open. They are people who are on a particular kind of mission in life when they reach out to help others. But it's still a mission - and the words sometimes hurt. Super-hero parents aren't afraid to tell us when we're wrong. And they tell us often - because we're often wrong.

And they tell us when we're wrong because they are protecting us every minute of every day - and, by us, I mean all of us.

It's one thing to recognize that your own child needs to be protected. That's not parenting; that's instinct.

But to reach out toward all the children in the world who might benefit from protection - to stand up and refuse to let kids other than your own be hurt ... that's being a super-hero.

It's not just keeping yourself and your child safe. It's about shielding the rest of the world, too.

And more than just shielding the rest of the world ... it's about where those shields come from.

Great parents can hold up shields and protect their kids ... and even, sometimes, the kids of other people's families by happenstance or coincidence or societal bonds. But for there to be a way that a parent can help protect and safeguard all the children of the world? No such shields often exist.

And that's why super-hero parents make their own.

Super-hero parents are the ones who build a shield out of nothing to protect all children, not just their own. They build them out of the energies that burn within them. They build them from the experiences and pains of the past. They build them from their fiery dedication to a better world. They build them out of the pain they experience on Earth, perhaps from their own lives ... or perhaps from the empathy they feel when their own children suffer ... or when the children of others suffer.

Their power is one of the purest - and noblest - application of the concept of defense.

And they defend because it's the right thing to do - no matter who is being defended, like them or not.

And a super-hero parent recognizes that this function of being a defender for their own children and for others' is an ongoing process.

It isn't something that just comes out of nowhere. And these parents recognize that it is a product of all of those tough life-experiences, not just the ones they can't figure out a way to get out of or to keep their child from experiencing. They recognize that they, themselves, are a work in-progress, and approach that not so much without fear but with a willingness to feel fear and to step beyond it. They recognize that there are parents out there who may be just starting out on that road, who may be inexperienced and struggling.

And, instead of feeling superior, they reach out toward them - even if that super-hero parent is at the beginning of their story - just starting to learn, themselves.

And super-hero parents know, too, that there will be wounds and scars from being a parent.

They know the process won't be without injury.

They know that they will, eventually, be totally changed by being a super-hero parent.

They know that the threats in the world that might harm children can take on a near-infinite number of forms, and they do not recoil from the challenges.

Because they also know that every fight can - some day - be won, no matter how challenging it might seem ... and no matter how insurmountable - even if - and especialyl when - that fight is not specifically their own.

And they can do all this without worrying about themselves, because a super-hero parent knows that how they're perceived doesn't matter. The act of protection is what matters.

And they know they may be maligned or seen in a bad light for doing what's right for their children and the children of others' ... and they fight on anyway.

They fight on no matter what their own shape or form is, or how they might not seem to fit the pattern of everything else around them.

And they do it even when the whole world seems to be attacking them for what they know is right.

In fact, they often do it specifically so they will be the target, and not their children.

They're willing to draw the fire, and then to even ask for more. And that doesn't scare them.

And these super-hero parents also know how to do so many different things, all at once, in fighting that all-important fight.

They know that the tools that worked today may not function tomorrow, and so they are always working to innovate and evolve.

And they know that what was for defense yesterday may someday need to be a weapon instead, whether they like it or not.

And they know that a super-hero parent can never be stationary ... can never hold still.

Because the world isn't holding still around them.

Because a super-hero parent knows that they have to keep moving, to keep traveling, to keep traversing a world of ever-changing threats and situations that require the utmost skill - and an ever-positive outlook - to even hope to navigate.

So, by now, a person might be getting the idea that I'm suggesting super-hero parents are somehow perfect.

That's not what I'm saying at all. Stress and challenges and fatigue can get to a super-hero parent just like a regular everyday parent ... because super-hero parents are regular, everyday parents - with the critical difference that a super-hero parent recognizes they don't have the option to give up.

But the difference is that when a super-hero parent has to scream at the unfairness and cruelty and wrongdoing in the world, they use that scream to marshal the troops.

And when they scream, the world hears them. Because it must.

And when they call, the troops come to them. Because they must.

And when they wind up on the ground, they use that as a new perspective - a new position from which to launch a fresh attack against the world's injustices, instead of as a cause for despair.

And they network.

Oh, wow -

do they ever network.

In fact, they build networks. They construct them right there, out of nothing but their own willpower and determination. And they keep on building in other ways, too.

They don't just read books on parenting. They write them. They don't just visit websites on parenting. They create them. They don't just talk about parenting. They craft speeches and presentations and symposiums and conventions and committees ...

... and, when it's called for, they even lecture. And they can lecture anyone - and I mean anyone.

And they do all these things even when they don't necessarily have the skills to do so built into their histories. They do so when it's needed - whether they know how or not. And they know the results might not be perfect, but they know that it has to be done - and that the process of learning is something they are also sharing with their children, helping them gain empathy for what their kids are going through by immersing themselves in the unfamiliar and reminding themselves what it's like to be in the middle of uncharted territory.

And, like their kids, they thrive in that territory.

And they find that they've grown into new roles, new identities, like putting on new uniforms that represent new duties and new roles they never knew they had inside of them - but which they undertake nonetheless because there's a need out in the world.

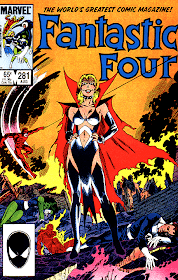

And what's even more amazing is that they so often do this in a very specific and particular way that brings up the reason why I have used the image of Sue Storm and dedicated this piece about Sue to these super-hero parents.

And here's why:

Superhero parents - no matter their roles - are often invisible.

And that's because super-hero parents aren't looking for glory, aren't looking for fame ... and aren't looking for notoriety.

They're doing what must be done because it must be done - and it's as simple as that.

Because no true parent wants to eclipse their child. Rather, a real parent wants their child to be the one who takes the stage, the one getting the positive attention of the world, the one gaining strength and confidence and the ability to look upon themselves with real pride.

So super-hero parents fight and scream and battle and war and defend and attack - and, so often, do it all invisibly, thanklessly, knowing the only real validation they will get is when they see a world where children who dealt with the crises their own kids dealt with aren't suffering any more.

And, for these invisible parents, that will be enough.

But it shouldn't have to be.

We should reach out and thank these parents for fighting this fight. We should join them, in fact. We should speak now, and thank them for what they do, because we don't always see how hard they're fighting, and how many opponents they're facing.

We should reach out to parents like the folks who write blogs like Lori Duron, Kelly Byrom and Sarah Manley. If you don't know who they are, then increase your awareness in the world. Visit them and hear what they have to say. Learn - and become a better parent. Find where you are on that scale I discussed, and if you're average - or good - or even great ... then, extend yourself until you're a super-hero like them.

There are so many real-world super-parents and real-life struggles that need to be shown to that real world. And if you're fighting those battles, invisibility can be a weapon. But, as Sue Storm knows, so can being wholly and completely visible.

No comments:

Post a Comment